DIPUTACIÓN DE HUESCA, 1998

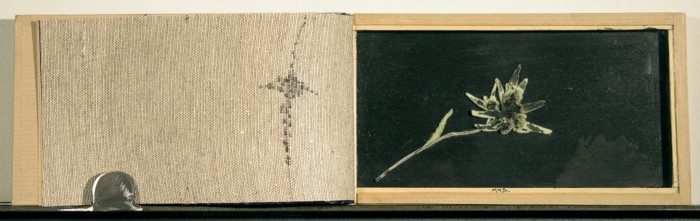

Libro nº 401

FLOR DE NIEVE NEGRA

1990. 115 x 207 x 18 mm

2 páginas de papel de calco y 2 de lienzo

Caja con edelweis procedente de Benasque, Huesca

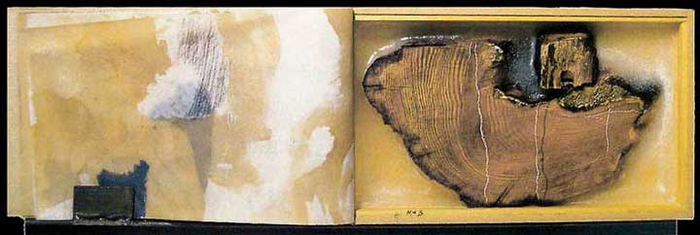

Libro nº 437

EL PINO DE LAS TRES CRUCES

Agosto de 1991. 157 x 258 x 46 mm

6 páginas de papel vegetal pintadas con barniz

Caja con resina, fragmento del Pino de las Tres Cruces

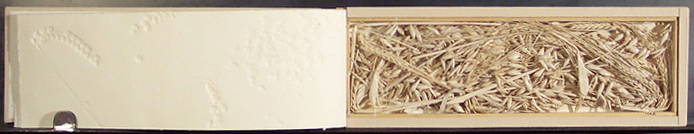

Libro nº 502

ACÍCULAS CELTAS

1.11.1992. 176 x 264 x 44 mm

6 páginas de papel de Nepal con estampación de sellos de hojas de pino

Caja con raíz de alcornoque, piedra, acículas del castro de Citania de Briteiros (Portugal) y círculo de madera quemada sobre cera

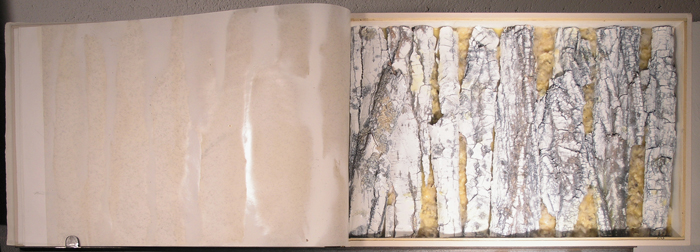

Libro nº 583

LAS RAÍCES DEL CIELO

25.8.1994. 395 x 592 x 30 mm

2 páginas de papel de yute resinado

Caja con raíces de pino y resina

Libro nº 667

SOLSTICIO VERNAL

12 5 1997. 154 x 274 x 29 mm

6 páginas de papel verjurado y papel vegetal gris con auras de hojas de chopo

Caja con semillas lanosas del chopo a la entrada de la cuesta del estudio del artista en Cercedilla

Libro nº 669

CERES

21.5.1997. 134 x 309 x 30 mm

4 páginas de papel de grabado con gofrados de avena y cebada

Caja con espigas de avena y cebada de Aguilar de Campoo y pintura blanca

Libro nº 671

CHOPERA BLANCA

11.6.1997. 430 x 641 x 65 mm

2 páginas de papel de grabado con gofrado de ramas de chopo y 2 páginas de papel vegetal con hebras con auras blancas de chopo

Caja con cortezas y semillas lanosas de chopo y pintura blanca

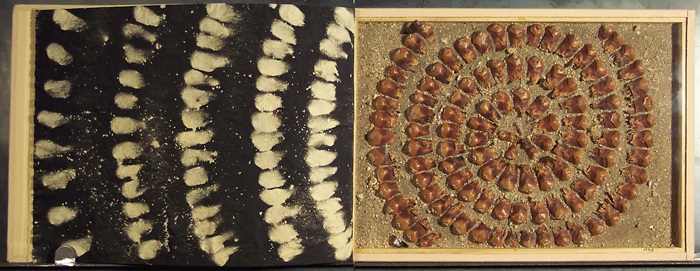

Libro nº 675

OPIOS

8.7.1997. 492 x 492 x 34

2 páginas de papel de kozo grueso con huellas y auras de amapolas blancas

Caja con 39 cazoletas de opio toledano sobre cera

Libro nº 697

ROTACIÓN EN EL PINO DEL ARENAL

7.1.1998. 300 x 421 x 28 mm

2 páginas de papel francés de paja hecho a mano con aurografías de escamas de piña

Caja con espiral de 106 escamas y dos semillas de Pinus Pinea sobre arena de río

Libro nº 698

CORO

31.1.1998. 300 x 300 x 66 mm

2 páginas de papel verjurado azul y 2 páginas de papel de algodón imitación Amate con aurografías y xilografías

Caja con setas de cornisa (Coriolus Verdicolor), rotulador y cera verde

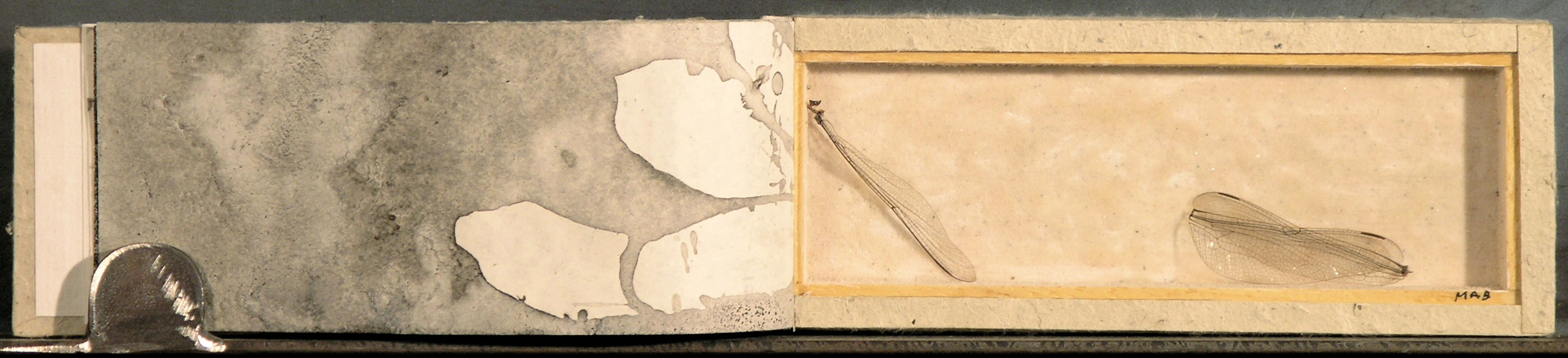

Libro nº 700

NIEVE A TRAVÉS DE ALAS DE LIBÉLULA

2.2.1998. 68 x 273 x 23 mm

6 páginas de papel reciclado con tinta china y nieve derretida

Caja con tres alas de libélula y sílice

JAVIER MADERUELO

Las obras de Miguel Ángel Blanco tratan sobre un tema único: la naturaleza.

La manera de entender la naturaleza y los conocimientos que el artista posee sobre ella no son de índole teórica, sino que tienen un origen empírico basado en el hecho de que Miguel Ángel Blanco trabaja “sobre”, “en” y “con” la naturaleza. Sin embargo, su relación con ella no es instrumental, no es un artista que simplemente se sirve de elementos o formas naturales, sino que a través de su trabajo establece unos fuertes lazos con la naturaleza, que podríamos calificar de espirituales.

Por lo tanto, para él la naturaleza no es una idea filosófica, un paradigma científico o una entelequia del cono cimiento, sino algo que emana del medio físico, del lugar en el cual habita, al cual, como persona y como artista, pertenece.

HUIR DE LA CIUDAD

Hay que empezar por aclarar que el lugar en el que habita Miguel Ángel Blanco, al contrario del que ocupamos la mayoría de los europeos, no es urbano. La circunstancia de haber elegido vivir, desde muy joven, al borde de un inmenso pinar en el hermosísimo valle de la Fuenfría ha determinado, sin duda, su idea de la naturaleza como medio en el cual él se halla inmerso.

Elegir como entorno vital el campo y no la ciudad, al final del siglo, cuando la mayor parte de la población europea es totalmente urbana, significa tomar una decisión trascendente que, sin duda, ha generado una serie de pautas de conducta personal que acaban reflejándose en la obra y la dotan de un carácter determinante.

El arte, como expresión de la habilidad técnica del hombre, de su capacidad para generar artificios, surgió en el ámbito urbano. Así, el artesano y el artista, frente al agricultor, el leñador y el pescador, son personajes urbanos cuyo trabajo tiene sentido en la ciudad, en la que se produce y merca la obra. Desde el Renacimiento, manifestaciones artísticas como la arquitectura, el teatro, la escultura y la pintura recrean las imágenes, las costumbres y los dramas de la sociedad urbana, de la vida civil.

El jardín como construcción arquitectónica, el poema bucólico como narración pastoril, el paisaje como género pictórico, y, a veces, la sátira como representación escénica, parecen negar este anunciado carácter urbano del arte occidental. Estas manifestaciones artísticas se centran en la recreación de escenarios y acciones campestres, pero, tanto el jardín más paisajista como el cuadro que recrea de la forma más naturalista el rincón de la campiña no pasan de ser representaciones que evidencian cierta ansiedad de la sociedad occidental. Esa ansiedad generó la idea de la recuperación de un “paraíso perdido” que los espíritus románticos recrearon con el fin de aliviarse del sofoco que provocaban las convenciones sociales surgidas e n el artificioso medio urbano.

Cuando Virgilio, tras abandonar la milicia y establecerse en el campo, escribe las Bucólicas recreando un escenario pastoril, no hace más que añorar lo que hubiera podido o debido ser una auténtica vida en el campo, que nunca tuvo, una vida en contacto con una naturaleza que ya era imposible en el siglo primero de nuestra era, porque el campo en el que se instala Virgilio está dividido en parcelas y polucionado por las acciones y los artificios de hombres urbanos, como él, que han impuesto un orden aprendido en la milicia a la naturaleza para dominarla.

Cuando, veinte siglos después, Miguel Ángel Blanco vuelve al bosque para habitar en él no lo hace con la añoranza de los virgilianos o de los románticos ni con la arrogancia de los conquistadores de territorios desconocidos sino que penetra en el bosque con la confianza de quien se encuentra en su casa.

La bulliciosa ciudad actual ha dejado una enorme huella en las diferentes tendencias del arte contemporáneo. En las obras de arte de este siglo se puede apreciar, entre otros rasgos, la influencia del ritmo frenético impuesto por la locomoción, la artificiosidad de un colorido surgido de la iluminación eléctrica, la tensión de ciertas composiciones equiparable al desquicio de las masas humanas que se aglomeran en los focos de atracción urbana. Por eso, elegir el campo como lugar de residencia, reflexión y trabajo supone intentar adoptar otro ritmo existencial y mirar con otra luz, aceptando depender directamente de fenómenos como el paso gradual de las estaciones, el trascurso diario del sol y la luna, la musicalidad del discurrir de los arroyos o la agresividad de una topografía que ha sido determinada por movimientos telúricos.

En pocas palabras, elegir el campo como forma de vida supone intentar bucear en los orígenes de una vida en la naturaleza y renunciar a lo logros histéricos de la civilización.

La idea de la necesidad de volver al seno de la naturaleza porque la civilización había corrompido al hombre fue enunciada por Jean-Jacques Rousseau en 1750 en su célebre ensayo titulado Discurso sobre las Artes y las Ciencias. Uno de los muchos seguidores de Rousseau, Henry David Thoreau, tras proclamar la desobediencia civil al Gobierno de los Estados Unidos, fue capaz de realizar el gesto heroico de retirarse de la civilización, abandonando la ciudad de Concord, para irse a vivir a una primitiva cabaña que él mismo se construyó en las orillas del lago Walden. En ese buscado retiro, escribió sus experiencias antiurbanas en el célebre libro titulado Walden, o mi vida en los bosques, publicado en 1854.

Las páginas de este libro muestran un gozo por la contemplación de la naturaleza, que es reclamado por Thoreau como un derecho. En este sentido, estas experiencias pueden ser apuntadas como una de las claves para acercarse al pensamiento y al trabajo estético de Miguel Ángel Blanco.

Pero no todo en el medio forestal es placentero y sosegado. La naturaleza se está transformando constantemente y lo hace, en muchos casos, de forma traumática, provocando catástrofes, unas veces pequeñas, como el desmoronamiento de la boca de un hormiguero, otras grandes, como un vendaval, la erupción de un volcán, una inundación o un incendio, fenómenos capaces de asolar vastas regiones. Esto también pudo comprenderlo Thoreau, que murió en 1862 como consecuencia de una tuberculosis provocada por las condiciones en las que vivió en su cabaña del bosque.

Efectivamente, Miguel Ángel Blanco no va a realizar un arte proselitista o de un ecologismo ramplón, narrando las ensoñadoras maravillas del bosque virginal o el dulce canto de los franciscanos pajarillos, sino que observará con cautela y respeto una naturaleza que tras una faz de belleza idílica ofrece aspectos que pueden ser también desoladores. Al artista, como al científico, no le está permitido criticar as acciones de la naturaleza, sólo analizarlas y comentarlas.

EL CAMINANTE SOLITARIO

De entrada, surge, creo yo, una primera pregunta: ¿qué tipo de arte es éste que practica Miguel Ángel Blanco? O ¿a qué genero pertenece?

Con frecuencia, cuando empleamos en término Land art solemos recordar las cautivadoras imágenes que aparecen publicadas en los libros y revista, aquellos enormes earthworks construidos en los desiertos americanos durante los años 70. Para muchos, Land art se identifica con esos trabajos en los que se han trazado líneas de varios kilómetros, se han terraplenado laderas o se han construido enormes masas de hormigón, pero, a pesar de que ese tipo de obras ha sido tipificado como Land art por la crítica, no constituyen más que un apéndice de una sensibilidad artística que se caracteriza, por el contrario, por un enorme respeto hacia la naturaleza y sus elementos y por una idealización de sus procesos.

Los artistas británicos, y en general los europeos, que trabajan dentro del ámbito del Land art se han caracterizado por desarrollar este tipo de sensibilidad. Ellos realizan obras que no suelen comprometer la fisonomía del paisaje y cuyo sentido es tomar conciencia de él y de sus cualidades físicas y emotivas.

Pasean por la naturaleza y actúan sobre el lugar sin apenas alterar sus elementos. Su trabajo consiste en observar el medio por el que caminan y en tomar algunas muestras, como piedras, palos, hojas o barro, cuando no unas simples fotografías, como hacen Hamish Fulton o Richard Long, elementos que sirven como testimonio de su presencia en la naturaleza.

Al igual que Long y Fulton, Miguel Ángel Blanco también es un artista que camina, un artista que extrae del acto de caminar la esencia de su obra. Pero Miguel Ángel Blanco no toma fotografías como Fulton o reordena elementos en el paisaje como Long, él recoge pequeñas muestras que busca y encuentra, infinitésimos despojos de los procesos de la naturaleza, como hojas, fragmentos de corteza, semillas, exudaciones de resina, restos de vendavales, setas, pequeñas piedras… y con ellos escribe libros sobre la naturaleza hasta completar una biblioteca que consta ya de más de 700 volúmenes.

Estos libros constituyen, ciertamente, un «arte del campo» que enlaza con lo mejor de lo que, tal vez impropiamente, pero sin ninguna duda, constituye el Land art europeo.

FENOMENOLOGIA DEL BOSQUE

El pinar de la Fuenfría o los bosques gallegos del Valle de la Mahia (donde ahora reside) no son sólo los lugares ideales que ha encontrado Miguel Ángel Blanco para vivir y desarrollar su trabajo sino que constituyen también una inagotable fuente de temas y de elementos creativos. Si se observa con una mínima atención el medio forestal nos daremos cuenta inmediatamente de que en él se puede encontrar una inagotable cantidad de especies botánicas y animales, una enorme variedad de piedras y rocas, con formas, texturas y colores sorprendentes, y sobre todo, que en él suceden fenómenos simples y complejos que van desde la caída de una piña al fluir misterioso de las aguas, desde la lenta formación de las cordilleras a la polinización de las plantas con la ayuda de los insectos.

De la misma manera que se suele ilustrar metafóricamente cómo la caída de una manzana despertó la curiosidad investigadora de Isaac Newton, la caída de una piña podría servirnos para ilustrar de qué manera el joven Miguel Ángel Blanco comenzó a interesarse por la fenomenología del bosque, interpretándola en términos estéticos.

Ciertamente, un aliento muy distinto va a animar el pensamiento científico de Newton y las acciones artísticas de Miguel Ángel Blanco y, sin embargo, ambas determinaciones van a tener un mismo fin: comprender la naturaleza, mostrando, a través de una formulación, sus fenómenos.

Si la formulación newtoniana puede ser calificada de física, la de Miguel Ángel Blanco lo será de psíquica, ya que, mientras que la primera atiende a las evidencias mecánicas de la atracción gravitatoria, la segunda pretende mostrar lo que hay de anímico y emocional en ciertos fenómenos de la naturaleza que el artista ha vivido.

Pero no deseo ahora enredarme en la casuística psicológica del arte sino, por el contrario, lo que deseo es señalar lo que hay de formulación en el trabajo de Miguel Ángel Blanco, lo que hay en su obra de escritura, de conjunto de signos organizados por medio de estructuras simbólicas.

Además de una enorme variedad de elementos naturales, en las obras de Blanco encontramos imágenes gráficas que han sido dibujadas, teñidas, pintadas o grabadas pero, que en rigor, estas obras no pueden ser calificadas de pinturas o dibujos convencionales y, aunque utiliza clara y sabiamente las técnicas de estampación, las obras en las que han sido empleadas estas técnicas no son sólo grabados.

Por otra parte, estas obras están construidas con objetos que han sido compuestos y ensamblados, con elementos sólidos y tridimensionales que ocupan un lugar en el espacio y sin embargo, no pueden ser tampoco calificadas estrictamente como esculturas.

¿Qué son? Tal vez, el término que mejor define la ontología de sus obras es la palabra libro y la manera de nombrar el conjunto de su trabajo se ajusta perfectamente al término biblioteca.

Los términos libro y biblioteca no son empleados aquí como metáforas sino que atañen a la identidad de las obras y nombran con propiedad lo que estos objetos son física y conceptualmente.

LA ESCRITURA NATURAL

La idea de que las obras de un artista plástico son libros nos induce a formular algunas nuevas cuestiones: ¿qué tipo de escritura es ésta? ¿cuál es su gramática y formulación?

Estas obras son, indudablemente, libros, y lo son no sólo por las similitudes de su apariencia externa, de la forma de sus volúmenes, de que estén conformados con tapas y hojas que se suceden y permiten ser pasadas. La apariencia de libro que tienen, sin embargo, es necesaria para que el espectador o, mejor, el lector de estas obras comprenda inmediatamente que son, en realidad, auténticos libros. Pero conseguir la apariencia de libro no es un fin en sí mismo.

Todo libro tiene como objeto narrar un relato y en este sentido es en el que se puede, con toda propiedad, denominar a estos volúmenes libros. Pero si la esencia de un libro es narrar, ¿qué cuentan o qué relatan estos libros?

Muchos sentidos podemos atribuir a su escritura. El primero de ellos tal vez sea el intentar poner orden a la variedad de elementos, seres vivos y fenómenos que forman ese conjunto heterogéneo que, para simplificar, denominamos naturaleza.

Éste es el sentido primigenio de la escritura, el de ordenar hechos e ideas con signos grabados. Con afán casi taxonómico, como un Adán contemporáneo, Miguel Ángel Blanco ha ido nombrando cada rama, cada trozo de corteza, cada acícula, cada gota de resina en diferentes libros que, de forma sistemática, ha dedicado a los bosques y forestas, tanto del pinar de la Fuenfría como de los más recónditos lugares.

Pero, al contrario que Linneo, que pretendió una catalogación universal, ordenada en especies y géneros, según los órganos reproductores de animales y plantas, Miguel Ángel Blanco ordena estas muestras de una manera que le resultará caprichosa al naturalista. No podría ser de otra manera. La diferencia entre el conocimiento de la ciencia y el que proporciona el arte estriba en esos matices de orden, en esas diferencias clasificatorias. El orden que sigue Miguel Ángel Blanco en la confección de sus libros es poético, vivencial, emocional.

En las páginas grabadas y en los recintos encajonados de estos libros se cuentan auténticas historias del bosque, se narran epopeyas meteorológicas, como vendavales o eclosiones primaverales, se constatan desastres, como incendios o sequías, y se cantan también los frutos de la foresta.

Miguel Ángel Blanco escribe esta historia natural en un lenguaje cuyos códigos no vienen dictados por las convenciones del abecedario y la gramática sino que son impuestos por la propia naturaleza.

En toda escritura jeroglífica, el signo sustituye al objeto, siendo el objeto representado por el signo. Sin embargo, en la escritura utilizada en los libros de la biblioteca del bosque los objetos son representados por sí mismos pero, al ser la corteza del alcornoque representada por un fragmento de corcho, ese trozo deja de ser fragmento concreto para convertirse en elemento de un sistema sígnico de escritura, para transmutarse en un signo que representa, sucesivamente y por extensión, a todos los corchos, todas las cortezas, todos los alcornoques, todos los árboles, todo el bosque, toda la naturaleza…

Efectivamente, toda la naturaleza se encuentra encerrada en la escritura de cada uno de estos libros. Esta escritura hermética, capaz de acumular y transmitir saberes personales sobre los eternos misterios de la naturaleza, nos pone en relación con cierto respeto religioso, con ciertos ritos privados que el artista necesita cumplir para formular su discurso y ejecutar su obra.

El bosque lo forman una serie de ídolos que, por su porte, su presencia física o su magnificencia, reclaman un respeto al caminante. Una escarpada roca o un árbol centenario son algo más que un simple hito de referencia, son los monumentos que expresan el poder de la naturaleza. Pero, muchas veces, ese árbol imponente, esa roca característica o ese arroyo proceloso tienen un nombre, una identidad concreta que han conseguido ganar por su carácter de ídolos, entonces se los saluda como lo que son, como los auténticos señores del lugar.

Pero además, el bosque, lugar sagrado para las primitivas culturas, es morada en la que habitan unos espíritus tutelares a los que tanto el leñador como el artista deben respetar si desean realizar sus respectivos trabajos.

Los monumentos naturales y los espíritus del bosque reclaman unos derechos al visitante de la foresta que se plasman en una liturgia reverencial que no sólo atañe a la manera de penetrar en el bosque y de recorrerlo, acciones que hay que realizar con respeto y admiración, sino, y sobre todo, que obliga a quienes han entrado con intención de tomar algunos de sus elementos, de recoger sus restos, de arrancar las hojas, de cortar las ramas o, simplemente, de mover una piedra del suelo.

A través de estos rituales, el artista aprende a estar atento, a escuchar los ecos de la caída de las piñas, a oír el viento correr entre las ramas, a seguir el fluir del agua en los arroyos, actos necesarios para poder escribir esta historia con los propios signos que la naturaleza ofrece, a través de las cortezas de los árboles, las acículas de los pinos, la resina de los troncos, las setas que levantan la hojarasca del suelo, el musgo que se adhiere a las rocas o el polen que tapiza el suelo.

Los libros que ahora presentamos son cuadernos de bitácora de esta travesía ritual, son diarios de viajero, de andarín que recorre los parajes, que observa la naturaleza y transmite, en un lenguaje emocional, estas sensaciones al público que quiera contemplar las obras.

JAVIER MADERUELO

The works of art by Miguel Ángel Blanco are about a unique theme: nature.

The way to understand nature and the knowledge that the artist has about it are not of a theoretical character but of an empirical origin based on the fact that Miguel Ángel Blanco works «in», «on» and «with» nature. Nevertheless, his relationship with it is not instrumental. He is not an artist who simply uses natural elements or shapes, but through his work establishes strong links with nature, which we can classify as spiritualistic.

Therefore, for him, nature is not a philosophical idea, a scientific paradigm or an entelechy of knowledge, but something that emanates from the physical medium, from the place in which he lives, to which as a person and as an artist he belongs.

ESCAPE FROM THE CITY

We have to start by clarifying that the place where Miguel Ángel Blanco lives, contrary to that occupied by the majority of Europeans, is not urban. The circumstances which caused him to choose, from a very young age, to live on the edge of an immense pine forest, in the most beautiful Fuenfría Valley, has determined, without doubt, his idea of nature as a medium in which he has immersed himself.

To choose the countryside as a vital environment, and not the city, at the end of the century, when the majority of the European population is urban, means to make a transcendental decision. This, without doubt, has generated a series of guidelines of personal conduct reflected in the work of art and endows it with a determining character.

Art, as an expression of the technical ability of man, in his capacity to generate artifices, arose in the urban atmosphere. Therefore, the artisan and the artist as opposed to the farmer, the lumberjack and the fisherman are urban characters whose work makes sense in the city, in which the work of art is produced and sold. Ever since the Renaissance period artistic demonstrations such as architecture, theatre, sculpture and painting recreate the images, the habits and the dramas of the urban society of civilian life.

Gardens as an architectural construction, bucolic poetry as a pastoral narration, landscape as a pictorial genre, and sometimes, satire as a scenic performance, seem to negate the aforementioned urban character of Occidental art. These artistic demonstrations are centered in the recreation of rural scenery and actions. Both the most picturesque garden, as well as the picture that recreates a corner of the countryside in the most naturalistic form, do not give way to being representations that make evident a certain anxiety of the occidental society. This anxiety generated the idea of the recuperation of a «lost paradise» which the romantic spirits recreated to ease the suffocation that the social conventions provoked, originating in the artful urban medium.

When Virgilio, after finishing his military service and establishing himself in the countryside, wrote The Bucolics recreating a pastoral scene, did not do more than miss what could have been or should have been a real life in the country, that he never had, a life in contact with nature which was already then impossible. In the first century of our age, the countryside in which Virgilio installed himself was divided into plots and polluted by the actions and the artifices of urban men, like him, who had imposed an order on nature, learnt in the military service. This enabled them to dominate it.

When, twenty centuries later, Miguel Ángel Blanco returned to the forest to live in it he does not do it with the yearning of the Virgilians or of the romantics nor with the arrogance of the conquerors of unknown territories. He enters the forest with the confidence of one who feels at home.

The bustle of the modern city has left an enormous mark in the different tendencies of modern art. In the works of art of this century, you can appreciate, amongst other traits, the influence of the frenetic rhythm imposed by locomotion, of the artfulness of colour suggested by electrical illumination, the tension of certain compositions. Comparable to the disturbances of the human masses that crowd together in the spotlights of urban attraction. Because of this, to choose the countryside as a place of residence, reflection and work means to try to adopt another existing rhythm and look again. This means accepting the fact to depend directly on phenomena such as the gradual passing of the seasons, the normal occurrence of night following day, the musicality of the flow of the streams, the aggressiveness of a topography that has been determined by tellurian movements.

In a few words, to choose the countryside as a way of life means to try swimming in the beginnings of a life in nature and renounce the hysterical achievements of civilization.

The idea of the necessity to return to the to the bosom of nature because civilization had corrupted man was enunciated by Jean-Jacques Rousseau in 1750 in his famous essay titled Discours sur les sciences et les arts.

After proclaiming the civil disobedience to the Government of the United States, Henry David Thoreau, one of the many followers of Rousseau, was capable of realizing the heroic gesture of retiring from civilization. He did this by abandoning the city of Concorde, to go to live in a primitive cabin, which he himself built, on the edge of Lake Walden. In this sought for retreat, he wrote about his anti urban experiences in the famous book titled Walden: or Life in the woods, published in 7854.

The pages of this book show an enjoyment of the contemplation of nature, which Thoreau reclaims as a right. In this sense, these experiences could be pointed out as one of the ways to get near to the thinking and to the aesthetic work of Miguel Ángel Blanco.

Nevertheless, not all in the forest is pleasure and peace. Nature is constantly changing. It does this, in many cases, in a traumatic form, provoking catastrophes, which are sometimes small as in the decay of the entrance to an anthill- at other times these are as big as a storm, the eruption of a volcano, a flood or a fire. These are catastrophes, which are capable of ravaging vast areas. Thoreau, who died in 1862 because of an attack of tuberculosis provoked by the conditions in which he lived in his cabin in the forest, could also understand this.

In fact, Miguel Ángel Blanco is not going to accomplish a proselyte style of art or an uncouth ecology, narrating the dreamy marvels of the virginal forest or the sweet singing of the little Franciscan birds. He is going to observe with stealth and respect a nature that behind a mask of idyllic beauty offers aspects that can also be desolate. The artist, as the scientist, is not allowed to criticize the actions of nature, only analyze them and comment about them.

The SOLITARY WALKER

Straight away, I believe, arises a first question. What type of art is this, which Miguel Ángel Blanco does or to what category does it belong?

Frequently, when we use the term Land Art we usually remember the captivating images of those enormous earth works, built in the American deserts during the 70s, which appear published in books and magazines. For many, Land Art is identified with those projects in which lines of various kilometers in length have been plotted, hills have been banked or enormous mounds of concrete have been built. In spite of these types of constructions having been typified as Land Art by the critics, they do not constitute more than an appendix of an artistic sensibility characterized, on the contrary, by an enormous respect towards nature and its elements and by an idealization of its processes.

The British artists and in general the European ones who work within the scope of Land Art have been characterized by developing this type of sensitivity. They make works of art, which do not compromise the physiognomy of the scenery and whose sense is to take note of it and its physical and emotional qualities.

They walk through nature and they perform in the place hardly altering its elements. Their work consists in observing the medium in which they walk and in taking some samples, such as stones, sticks, leaves or mud, when they do not take simple photographs, such as Hamish Fulton or Richard Long do, elements which serve as witness to their presence in nature.

The same as Long and Fulton, Miguel Ángel Blanco is an artist who also walks, an artist who extracts from the act of walking the essence of his work. However, Miguel Ángel Blanco does not take photographs like Fulton or rearrange the elements of the countryside, as does Lung. He picks up little samples that he looks for and finds. These are infinitesimal spoils of the process of nature, such as leaves, pieces of bark, seeds, resin exudations, remains of storms, mushrooms, little stones… and with these writes books about nature until completing a library which consists of more than seven hundred volumes.

These books constitute, of course, a country art that links with the best of that which, maybe inappropriately, but without a doubt, constitutes the European Land Art.

THE PHENOMENOLOGY OF THE FOREST

The pine forest of the Fuenfría Valley or the Gallician forests of the Mahia Valley (where he now lives) are not only ideal places which Miguel Ángel Blanco has found to live and develop his work but also constitute an inexhaustible source of themes and creative elements. If one observes with a modicum of attention the forest medium, one can immediately realize that there can be found an inexhaustible quantity of botanical and animal species, and an enormous variety of stones and rocks, with surprising shapes, textures and colours. And, above all, there occur simple and complex phenomena that go from the falling of a pinecone to the mysterious flowing of the waters, to the slow formation of the mountain ranges and the pollination of the plants with the help of the insects.

In the same w ay that one would, usually metaphorically, illustrate how the fall of an apple awoke the investigating curiosity of Sir Isaac Newton, the fall of a pine cone could serve to illustrate in which way the young Miguel Ángel Blanco started to he interested in the phenomenology of the forest, interpreting it in aesthetic terms. Of course, a very different breath is going to encourage the scientific thinking of Newton and the artistic actions of Miguel Ángel Blanco and, nevertheless, both determinations are going to have the same end: understand nature, and, Shown through its formulation, its phenomena.

If the Newtonian formulation can be classified as physics, that of Miguel Ángel Blanco would be psychic. That is because whilst the former attend to the mechanical evidence of gravity attraction the latter tries to demonstrate that there are moods and emotions in certain phenomena of nature that the artist has lived.

But I do not wish to entangle myself in the casuistic psychology of art, but on the contrary, I do wish to point out what there is of Formulation in the work of Miguel Ángel Blanco, what there is of sets of organized signs through symbolic structures in his writing

Besides an enormous variety of natural elements, we can find graphic images that have been drawn, dyed, painted or engraved in the works of Miguel Ángel Blanco. These works of art cannot be classified as conventional drawings or paintings and although he uses clearly and knowledgeably the techniques of engraving, the works in which these techniques have been employed are not just printed.

On tile other hand, these objects have: been made and assembled, with solid and three-dimensional elements that take up space, but nevertheless cannot be classified strictly as sculptures.

What are they? Perhaps the term that best describes the ontology of his works of art is the word book and the way to name the whole of his work adjusts perfectly to the term library.

The terms book and library are not used here as metaphors but concern the identity of the objects and name with propriety what these objects are physically and conceptually.

The natural writing

The idea that the works of art of a plastic artist are books tempts us to formulate some new questions: What type of writing is this? What are its grammar and its formulation?

These works of art are, without a doubt, books, and they are so, not only for the similarities of their external appearance, of the form of its volumes, that are shaped with covers and leaves, that follow one another.

The appearance that they have of book form, notwithstanding, is necessary so that the spectator, or better, the reader, of these works of art immediately understands that they are actually authentic books. But to attain the appearance of a book is not the end achievement.

All books are made to tell a story and in this sense we can, with all property, name as books these volumes. But if the essence of a book is to narrate, what story do these books tell us?

Many meanings can be attributed to their writing. The first of these is perhaps to try to organize the various elements, living beings and phenomena that make up this heterogeneous whole that, to simplify things, is called nature.

This is the primogenital meaning of the writing: that of organizing facts and ideas with carved signs. With taxonomic travail, like a modern Adam, Miguel Ángel Blanco has named each branch, each piece of bark, each needle, and each drop of resin in different books. So that, in a systematic way, he has dedicated them to the forests and woods, both to the pine forest of Fuenfría as to the most recondite places.

But, contrary to Linneo, who tried a universal cataloguing, organized ill species and groups, according to the reproductive organs of the animals and the plants, Miguel Ángel Blanco organizes these samples ill a way that would seem fanciful to the naturalist. It could not be in any other x\ a\. The difference between scientific knowledge and that which art gives rests on these nuances of order, on these different classifications. The order that Miguel Ángel Blanco follows in the making of his books is poetical, experienced, and emotional.

In the engraved pages and the boxed enclosures of these books authentic stories of the forests are told, meteorological sagas such as storms or spring hatchlings are narrated, disasters such as fires or droughts are recounted, and the fruits of the forest are talked about.

Miguel Ángel Blanco writes this nature story in a language whose codes are not dictated by the conventions of the alphabet and grammar but are imposed by nature itself.

In all written hieroglyphics, the sign substitutes the object, the object being represented by the sign. Nevertheless, in the writing used in the books of the Forest Library the objects are represented by themselves. However, the fact that the bark of a cork oak is represented by a piece of cork stops this piece from being a concrete fragment. It converts itself in an element of the sign system of writing; it transforms itself in a sign that represents, successively and extensively, all types of cork, all types of bark, all cork oaks, all trees, all the forest, all nature….

Indeed, all nature can be found enclosed in the writing of each one of these books. This impenetrable writing, capable of accumulating and transmitting personal knowledge about the eternal mysteries of nature, reminds us of certain religious respect, of certain private rites that the artist needs to complete to formulate his address and execute his work of art.

The forest is composed by a series of idols that by their bearing, their physical presence or their magnificence reclaims a respect from the walker. A steep rock or a century old tree is something more than simply a reference milestone. They are the monuments that express the power of nature. But, many times, that imposing tree, that characteristical rock or that tempestuous stream has a name, a concrete identity that it has earned by its character of idols. Then we greet them as what they are, authentic lords of the forest.

But besides, the forest, a sacred place to the primitive cultures, is the abode in which live some tutelary spirits, which the woodsman as well as the artist should respect if they want to do their respective jobs. The natural monuments and the spirits of the forest reclaim some rights from the visitor that are shaped in a reverential liturgy. This not just concerns the way in which to enter the forest and to pass through it, actions that should be done with respect and admiration. Nevertheless, above all, to commit those who have entered with intention to take some of its elements, to pick up its remains, to pull out the leaves, to cut the branches, or, simply to move a stone from the ground.

Through these rituals, the artist learns to be attentive, to listen to the echoes of the fall of the pine cones, to hear the wind rush through the branches, to follow the flow of the waters in the streams. These acts are needed to write this story with the signs that nature offers. These are the bark of the trees, the needles of the pine trees, the resin from the trunks, the mushrooms that lift the leaves from the floor of the forest, the moss that adheres to the rocks or the pollen that covers the ground. The books that we now introduce are binnacle notebooks of this ritual crossing. They are diaries of the traveler, of the walker who goes through the places, who observes nature and transmits, in an emotional language, these sensations to the public that wishes to contemplate the works of art.